Illustration by Marcia Staimer

Ryan Johnson is a noodler when it comes to electronic gizmos. Give him a new device and he can’t but help explore the apps and coding to see how things work.

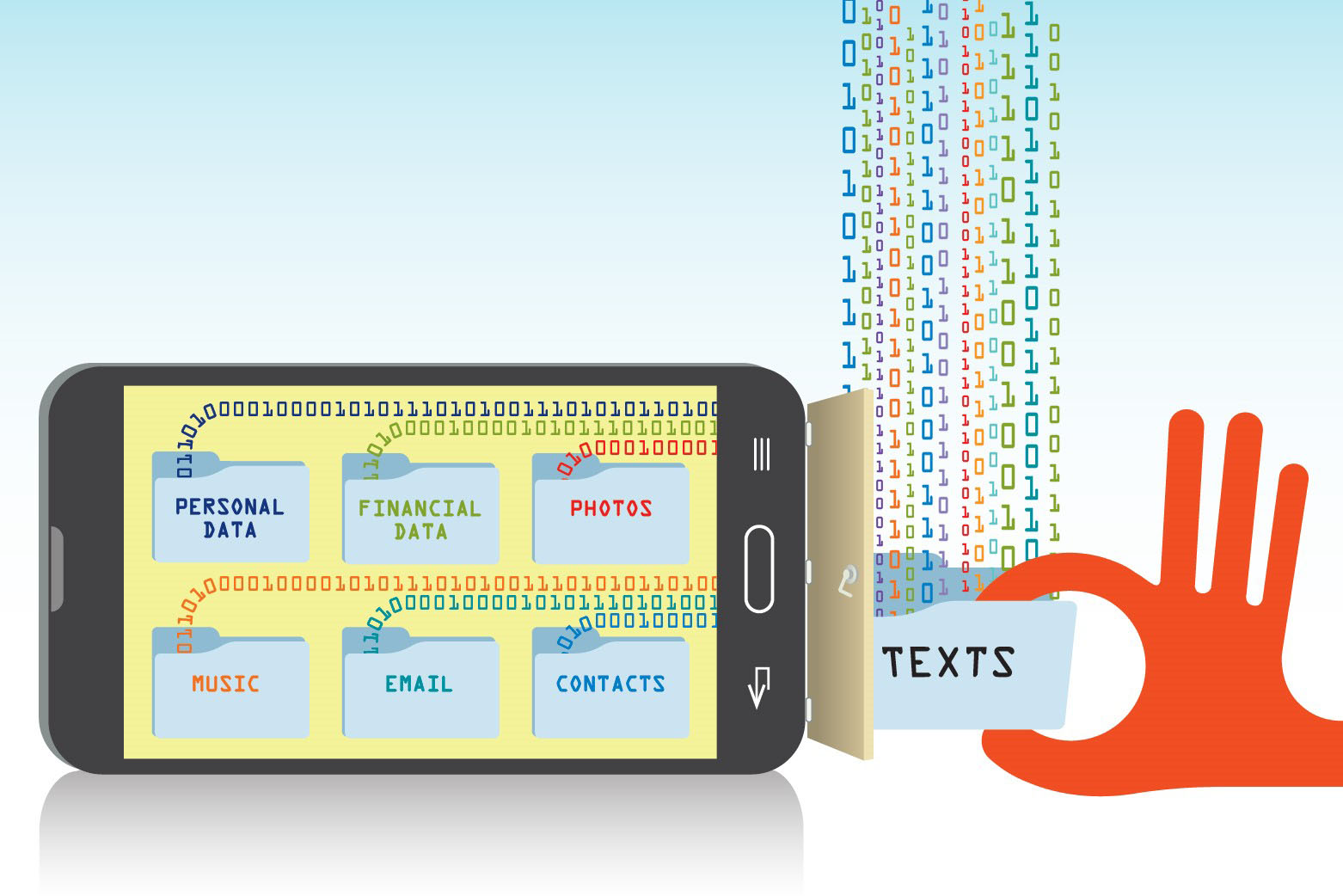

During one exploration of a phone he planned to use on a trip to Taiwan, Johnson discovered preinstalled software that every 72 hours sends all text messages to a server in Shanghai, China.

“Everyone around the office was ecstatic,” Johnson said. “It was probably the happiest day I’d seen there, so it was fun.”

The office was that of Kryptowire, a five-year-old company founded by Angelos Stavrou, director of George Mason University’s Center for Assurance Research and Engineering. The Fairfax, Va., company, which does mobile application security and analytics, employs 16 people, 14 of which are George Mason graduates, Stavrou said.

That includes Johnson, 34, and Brian Schulte, 28, both of whom have master’s degrees in information security and assurance from Mason and are Kryptowire’s co-founders.

“I’m a professor here. I have students. They graduate and come to me looking for jobs,” said Stavrou, an associate professor in the Computer Science Department of Mason’s Volgenau School of Engineering. “I’ve already worked with them. I know them. It’s easy.”

Uncovering the data swipe, which mostly affects international customers and users of disposable or prepaid Android phones, took three weeks of 14-hour days, Johnson said. What pushed him was the discovery of several lax security components and obfuscated code.

“It was looking like they were trying to hide something,” Johnson said.

The New York Times reported that the company that wrote the software, Shanghai Adups Technology Company, says the code runs on more than 700 million phones, cars and other smart products and was developed to help a Chinese phone manufacturer monitor user behavior. American phone manufacturer BLU Products told the Times that 120,000 of its phones were affected, though a software update eliminated the problem.

“The issue comes into play when big data starts to take effect,” Johnson said, “and that one piece of data, that mobile identifier that links you to your phone, is then linked to your name, which is linked to everything which you have done online.”

The discovery, which Stavrou said was reported to the U.S. government, brought much publicity to Kryptowire, especially through online tech media.

Although the company, with 20 to 30 clients, has no formal ties to Mason, the university’s imprint is all over it through its graduates working there.

“That it’s a good educational institution allows us to get guys that are that good,” Schulte said. “The programs and research departments that are available are really the key Mason is able to deliver on.”