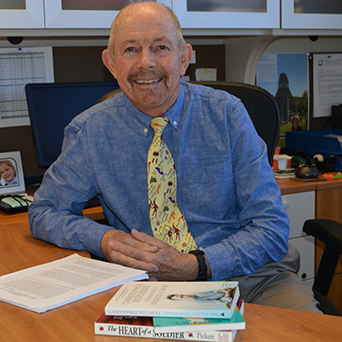

Mason Engineering's David I. Holmes uses statistics to investigate the authors of famous literary and historical documents.

In his latest literary detective work, a Mason statistics professor used special statistical methods to uncover a second writer who contributed to an important book in American history.

David I. Holmes, an assistant professor in Mason Engineering’s Department of Statistics, applied stylometry, the statistical analysis of literary style, to analyze Rights of Man written by Thomas Paine, a leading political philosopher and writer during the American Revolution.

Experts have suggested that a 6,000-word passage in the book wasn’t written by Paine but instead was penned by his friend the Marquis de Lafayette. The book argues that a political revolution is permissible when a government doesn’t safeguard the rights of its people.

Holmes and Richard Forsyth, a researcher in Great Britain, compared the two famous men’s “word prints,” which is the way people subconsciously use words such as “the,” “and,” “but,” “to,” and “from.”

“It’s quite surprising the way people use the little words, the humble servants of speech,” Holmes says. "By looking a large number of these words and their rate of occurrence, we can actually use statistics to detect who is the author with a high degree of accuracy.”

The researchers used three statistical techniques to analyze the book, and each showed that the passage in question was written by Lafayette. Their paper, “The Writeprints of Man: A Stylometric Study of Lafayette’s Hand in Paine’s 'Rights of Man,'” will be published this year in Digital Humanities Quarterly. Holmes says it’s logical that a portion was written by Lafayette because the two men were friends, and the passage concerns the French Revolution.

Department of Statistics Chairman William Rosenberger says this “fascinating research shows that statistics is useful and important in history and literature, like it is in other disciplines.”

Holmes, who has been using stylometry since the 1980s, earned his PhD at Kings College, University of London. There, he used statistical techniques to determine the author of the Book of Mormon, which he concluded was in Joseph Smith’s words. “I did that way back in the 1990s, when the techniques were pretty rudimentary. I could do it so much better now.”

Doing this type of research requires large chunks of 3,000 words or more, says Holmes, professor emeritus of the College of New Jersey, where he taught for 19 years. It doesn’t work with short writing samples.

When he’s researching the authorship of a document or book, he considers several possible candidates and compares their writing. For example, he analyzed The Heart of a Soldier: Intimate Wartime Letters from General George E. Pickett C.S.A. to His Wife to determine whether Pickett actually wrote the letters. “This was a great project. What it came down to is who wrote these letters: him or her?”

Pickett’s much younger wife, LaSalle Corbell Pickett, published the book after her husband’s death. She claimed the letters were written by Pickett from the field of battle, but historians suspected she wrote them because of historical inconsistencies in the text. For example, the book refers to Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg, but it wasn’t called that until after the Civil War.

Using a multivariate analysis of the writings of Pickett and his wife, Holmes concluded that she wrote the letters. “Maybe there is a germ of a letter there, but she authored these. They match her writing.”

She probably did it because she needed the money, and she wanted to improve her husband’s image after he died, he says.

On at least one occasion, Holmes hit a dead end. Last fall, he tried to determine the author of The Expert at the Card Table: The Classic Treatise on Card Manipulation by S. W. Erdnase. Many consider the book to be the definitive work on cheating at cards, but the writer appears to have used a pseudonym.

He investigated six or seven possible authors, but none of the candidates had word prints that matched the writing. However, he discovered the book was written by two people. “This was a tricky one. It’s the first one that has really stumped me.”

Two other potential candidates have recently emerged as possible authors, and he’s working to review their writings.

Next fall, he and an undergraduate student will investigate whether Davy Crockett is the author of a diary written during the fighting at the Alamo. “It’s thought by historians that he couldn’t have written the diary during his time at the Alamo.”

The field has changed since he began his work. “A lot more people who come in now are computer scientists, and they look at pattern recognition.”

But Holmes plans on sticking with statistical analysis. “We know that our methodology works.”